A paralegal is a legal professional who performs tasks that require knowledge of legal concepts but does not hold the full expertise of a lawyer with an admission to practice law. These skilled individuals play a crucial role in supporting lawyers and law firms across various legal domains.

Tasks and Responsibilities

Paralegals engage in a wide range of duties, assisting lawyers in their day-to-day work. Some common tasks include:

- Legal Research: Conducting research on case law, statutes, regulations, and legal precedents.

- Document Preparation: Drafting legal documents, contracts, and correspondence.

- Interviewing Witnesses: Gathering information from witnesses and clients.

- Case Management: Organizing case files, maintaining records, and tracking deadlines.

- Trial Preparation: Assisting in trial preparation by organizing evidence, witness lists, and exhibits.

- Client Communication: Maintaining professional communication with clients.

Distinction Between Paralegals and Lawyers

While lawyers analyse legal matters from various angles, considering implications, consequences, and strategy, paralegals focus on executing the course of action recommended by lawyers. Their work involves practical implementation, such as interviewing witnesses, conducting research, and completing legal paperwork.

Crossover with Lawyers

In some practice areas, paralegals handle cases from start to finish, especially when dealing with routine matters like conveyancing, probate, debt recovery, or small claims. However, lawyers continue to handle complex cases or those involving substantial sums of money, such as mergers, murder trials, and high-stakes divorces. Paralegals’ involvement in such instances tends to be peripheral.

Examples of Paralegal Work

Here are some real-world examples of paralegal tasks:

- Probate and Family Law: Handling divorce cases or probate matters within a solicitors’ firm.

- Property Transactions: Assisting in land purchases and property sales for development companies.

- Trademark Registration: Registering and defending trademarks for businesses.

- Animal Cruelty Prosecutions: Working with the RSPCA prosecutions team.

- Immigration Law Advice: Providing immigration law guidance to clients.

- Consumer Law Protection: Advising on consumer rights within local authority trading standards departments.

- Citizens Advice Volunteer: Assisting the public with employment, housing, and other issues.

- Crown Prosecution Service: Supporting legal proceedings.

- Company Incorporation: Handling company secretarial work for solicitors’ firms, accountancy firms, or company formation practices

Paralegal Links

Certainly! Here’s a curated list of UK-based paralegal websites that you might find valuable:

- Professional Paralegal Register (PPR): The PPR is a voluntary registered scheme and regulator for professional paralegals. Employers and the public can be assured that paralegals on the register meet required standards. Paralegals with a Paralegal Practising Certificate (PPC) are fully regulated to offer legal services to consumers.

- How to Become a Paralegal in the UK: This website provides insights into becoming a paralegal in the UK. It also highlights job opportunities advertised on platforms like Indeed and Reed.

- UK Law Blogs: Discover the best UK law blogs ranked by traffic, social media followers, and freshness. Stay updated on legal trends and news from these informative blogs.

- National Paralegal Register: If you’re looking for a paralegal to assist with a legal issue, use this register. You can shortlist paralegals based on region and legal expertise. Check if a paralegal is a NALP member using the filters.

In summary, paralegals are essential contributors to the legal field, bridging the gap between legal theory and practical implementation. Their expertise ensures the efficient functioning of legal processes and supports lawyers in delivering effective legal services.

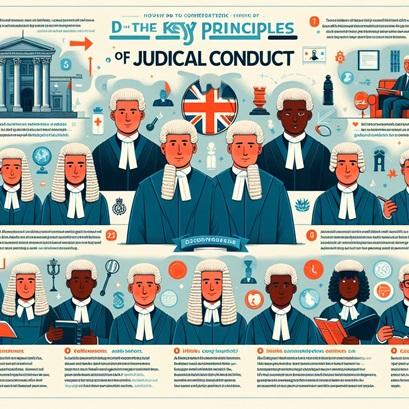

Check out our articles on Barristers, Direct Access Barristers, Four Inns of Court, Bar Standards Board, Bar Standards Board Justice ?, Solicitors, Rule of Law and the highly questionable Sussex Family Justice Board.

Read the reviews of Junior Sussex Barrister Gavin Howe

“He is awful, underhanded and should not be practising law!”

and Legal 500 Junior Barrister Eleanor Battie

“She is a one-woman legal A Team”

Latest Articles

- What is a Paralegal ?A paralegal is a legal professional who performs tasks that require knowledge of legal concepts but does not hold the… Read more: What is a Paralegal ?

- What is a Judgment ?A judgment, also known as a judicial decision or court ruling, is the final decision made by a court of… Read more: What is a Judgment ?

- What is an Adverse Inference ?Adverse inference is a legal principle that plays a significant role in various areas of law, including criminal, civil, and family law. It arises… Read more: What is an Adverse Inference ?

- BarristersA barrister is anyone who has been Called to the Bar in England and Wales. For a barrister to offer… Read more: Barristers